All the action has been along the Front Range. Could places like Craig, Fort Morgan and Pagosa Springs be part of the story going forward?

by Allen Best

Data centers in Colorado have been almost exclusively located along the Front Range, more narrowly yet between Colorado Springs and Boulder County.

In other words, they have arrived at exactly those places within the state that have prosperous economies, jurisdictions even struggling with the challenges imposed by growth.

Might data centers make their way to rural areas of Colorado?

Leaders of several electrical cooperatives offer mixed responses. Some report getting interest already, others not.

Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, Colorado’s second largest electrical provider, hopes to prime the pump. It has filed a proposal with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for a tariff that it believes will interest developers. It’s called HILT, which stands for high-impact load tariff. It is designed for demands of 45 megawatts or more.

Meanwhile, several state legislators continue to hone bills they expect to introduce into the next legislative session. In the last legislative session, one bill proposed incentives for data center development in some locations. Others thought that the state needed guardrails to ensure that other customers — as well as land and especially water resources — are not imperiled. (Look for a deeper story on that in coming days in Big Pivots).

“Absolutely,” said Duane Highley, the chief executive of Tri-State, in an interview with Big Pivots on Oct. 7 when asked about potential for data centers in places like Craig or Fort Morgan. “Our members have actually had quite a bit of interest across our entire footprint. So definitely not just the urban areas.”

The Westminster-based cooperative provides wholesale power to 40 electrical cooperatives and public power districts in Colorado and three adjoining states.

“Some of our high-elevation members get a lot of interest because of the cool air and less need for cooling a data center,” he said. This, he added, is particularly true in Wyoming, where Tri-State has 10 member cooperatives. It supplies electricity to 16 cooperatives in Colorado.

Tri-State does not deliver electricity to Craig and Hayden, although it does operate three coal-burning units at Craig. It plans a gas-fired power plant there after the coal units get retired. The first unit is scheduled to retire later this year and the final two before the end of 2028.

At 6,200 feet in elevation, Craig is consistently cooler than the Front Range. It is often below zero during winter nights, sometimes far below.

“I guess Craig would be an excellent spot,” said Highley. He cited the existence of a “really big substation” as well as transmission.

“So if anybody wants to start a conversation around Craig, we will have the tariff in place to allow that to happen. ”

Highley reported that Tri-State has had four gigawatts of requests on its system from data centers. Tri-State has a generating capacity of 2.5 gigawatts from Wyoming to Arizona. Not all that demand will materialize, Highley hastened to add. “A lot of them are just shopping, but I have to think that some part of that is real.”

A spot check by Big Pivots of electrical cooperatives in Colorado reveals little of substance — yet.

“We really haven’t had any inquiries about data centers in the Mountain Parks service territory to date,” said Virginia Harman, the chief executive of Granby-based Mountain Parks Electric. “That doesn’t mean they won’t happen.”

In Buena Vista, Jon Beyer, the general manager of Sangre de Cristo Electric, has the same report. “We are not getting any inquiries anywhere in the Arkansas Valley. Land prices are pretty expensive, and electrical infrastructure is probably not robust enough for stuff of that size. Finding employees is a challenge as well,” he said.

“Coops along the Front Range — Poudre Valley, United Power, Mountain View, maybe even San Isabel, I would guess they have all received inquiries, folks kicking the tires.”

In western Colorado, Delta-Montrose Association has at least heard a little bit of interest via upstream electrical providers but “nothing to take to the bank,” said Kent Blackwell, the chief administrative officer. “The fact that we have even heard any out there is shocking to me, this far removed from urban centers.”

Different sizes

Data centers do come in different sizes and flavors. Micro data centers generally are those in places of 5,000 square feet or less. Small comes in at 20,000 square feet. Hyper-scale data centers are classified as those with over 100,000 square feet and consuming 100 megawatts.

QTS, Colorado’s most high-profile data center, seems not to have divulged its square footage but has a 67-acre campus in Aurora, near the intersection of I-70 and E-470, and a demand of 177 megawatts. However, it still ramping up, with a 10-year expansion.

The QTS hypescale data center in Aurora occupies a campus of 67 acres and is still ramping up.

Many data centers are even larger. Meta (Facebook) has a data center in Oregon that covers 4.6 million square feet. A data center in Inner Mongolia covers 10.7 million square feet.

These definitions and other information, by the way, come in part from Google AI reports (which makes those of us who are actual providers of diminished relevance — or at least uncompensated.) They could be wrong — as AI often is. Of course, newspapers were never wrong, were they?

Tri-State’s Highley said he has talked with developers covered by non-disclosure agreements. “I can’t share who they are, but I’ll just say I’m inspired by them,” he said. “They have a lot of money, and they do have the ability to execute. I also believe they’re shopping multiple locations at once, and so it’s a little bit of competition.”

Will this new HILT tariff from Tri-State — assuming it is approved by FERC — become a model for others? Highley said he got a call from a White House office in late September. The individual had lots of questions about Tri-State’s FERC filing. The individual had read Tri-State’s FERC filing in detail.

“Why do you care so much? Why are you calling me?” Highley asked. ” And he said, ‘Because I think this tariff that you filed could set a precedent for the industry nation-wide.”

Highley said he has not noticed another large-load tariff approved at FERC, although he has seen two that were rejected. “I don’t think we have it perfect, but we think we’re moving down a good path. We had input from developers and from our own co-op members to design this.”

Stranded assets?

Will this interfere with Tri-State’s plans to decarbonize? It expects to be at 50% carbon free electricity by year’s end and 70% by 2030. No, said Highley. Tri-State can meet new demand with solar, wind and battery storage. It also plans another natural gas plant near Craig, pending approval by the Colorado Public Utilities Commission.

Tri-State and its members would also allow data center developers to produce part of their own generation. That tariff is called bring-your-own-resource, or BYOR. A developer might have better access to supply chains, Highley said. “Again, some of these hyper-scalers have such a big checkbook they can buy their way to the front of the line. ”

HIghley said the Tri-State’s tariff will ensure that it has the capacity to back up the data center developer while getting properly compensated, so no other members subsidize the project.

A September presentation by Matt Fitzgibbon, Tri-State’s vice president of planning and analytics, tells a slightly nuanced story. A slide deck reported “limited potential” for stranded assets resulting in financial risk to Tri-State and its members while enabling “economic development across our members’ systems at an unprecedented level and pace.”

This gets at the heart of one concern about data centers, as illustrated in the Xcel filing with the Colorado Public Utilities Commission last year. How much of the prospective demand from data centers is real? And if it is not real, who will be left holding the bag if a utility spends gobs of money building new generating capacity? How much risk will be put on ratepayers, in the case of Xcel, or in the case of cooperatives, members?

In Durango, Chris Hansen, the chief executive of La Plata Electric since November, foresees data centers arriving in more rural parts of Colorado.

“We have had significant discussions with three different data center operators who are interested in southwest Colorado,” he reported. “We are making sure that we are open for business and communicating our opportunities in the near term, in the next 24 months, and those requiring more lead time of three, four or five years.”

Data centers, he said, “are most focused on low cost of power and availability of water for cooling. Those are very high on their list.”

And Colorado’s sales tax policy will not make it a higher cost for developers when they are buying hundreds of millions of dollars for chips. “That is something that is relevant for them as they make their decisions.”

Hansen said he believes that data center demand can be met in ways that are highly beneficial to existing customers and the electrical system more broadly.

Some rural places could be limited by lack of sufficient fiber connectivity to more urban areas. Hansen acknowledges that but points out that data centers can have different needs. As for southwest Colorado, it is well connected.

Delta-Montrose’s Blackwell sees his cooperative being in a good position to interest data center developers. It has fiber connectivity to Denver, Salt Lake City and Albuquerque. “A Facebook, an Amazon — the big data centers will want direct fiber connectivity.”

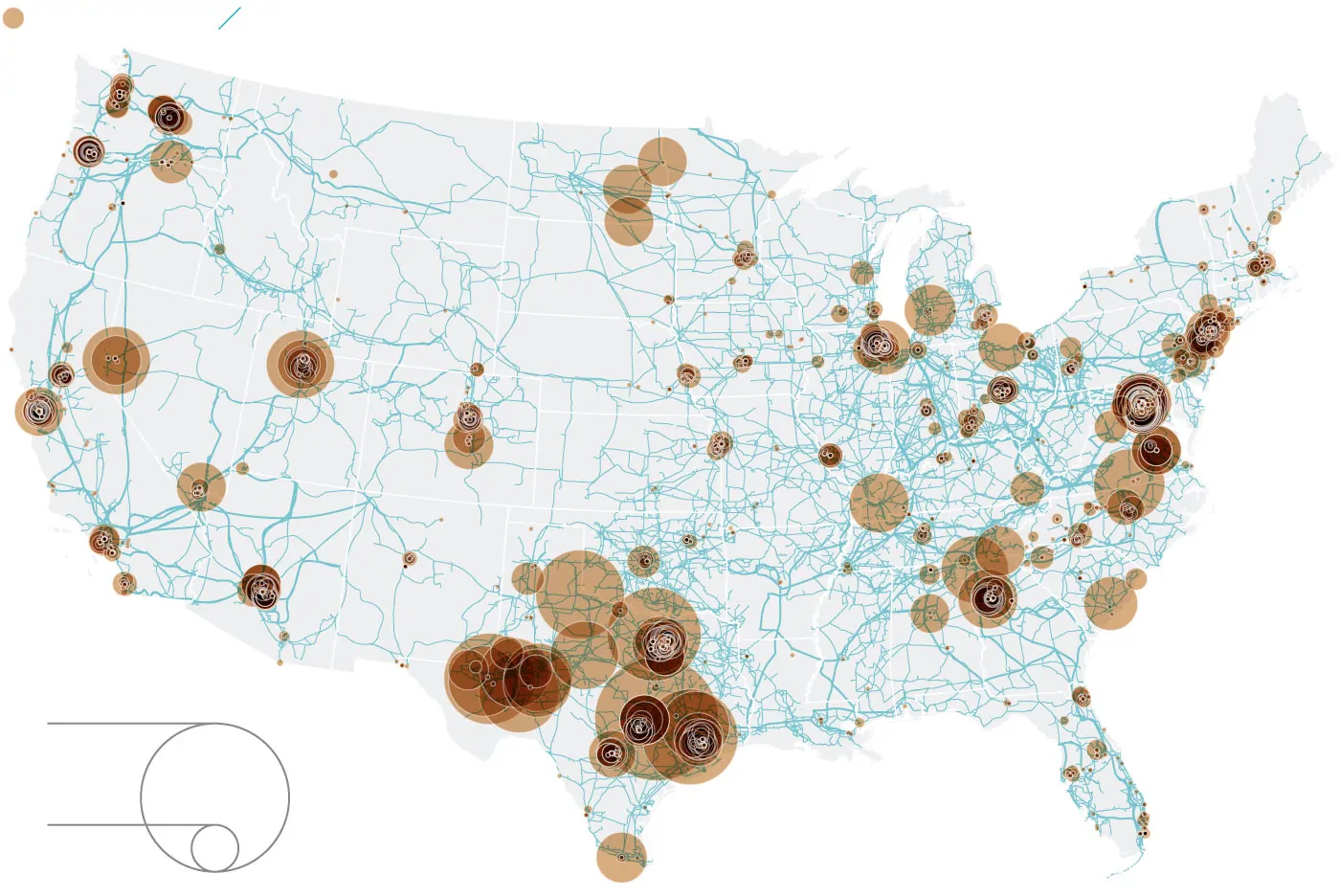

A map published last week by the Wall Street Journal using Department of Energy information showed data centers across the United States. Texas has, well, Texas-sized dots and maybe bigger. Virginia, with its data center alley, is well represented. But you see almost no dots of any size in the Rocky Mountain states beyond the urban areas with the exception of Cheyenne.

A map published last week by the Wall Street Journal using Department of Energy information showed data centers across the United States. Texas has, well, Texas-sized dots and maybe bigger. Virginia, with its data center alley, is well represented. But you see almost no dots of any size in the Rocky Mountain states beyond the urban areas with the exception of Cheyenne.

Hansen said he believes electrical cooperatives are positioned to meet demand that investor-owned utilities in urban areas cannot.

“Larger investor-owned utilities around the country are not in great position to meet demand. That is the trend I am seeing. Rural co-ops can move fast, as they don’t have to necessarily go through PUCs. Those things help make rural areas more attractive.”

Lots of shopping, little commitment

In Southwest Colorado, the data developers have been looking to get started at 50 to 100 megawatts. If things go well, they might want to grow to data centers of a gigawatt or more.

Data centers come in different flavors, said Hansen. Some data centers do have flexibility in their need for electricity, while others must respond immediately to needs of their consumers.

Then there is the bring-your-own power approach. The Wall Street Journal article on Oct. 15, “AI Data Centers, Desperate for Electricity, Are Building Their Own Power Plants,” noted the problems of building transmission and other infrastructure.

“Tech companies in the AI race need power, and lots of it. They aren’t waiting around for the archaic U.S. power grid to catch up,” reports Jennifer Hlller.

Data centers long took power for granted, a consultant told the Journal. “But that’s no longer possible given the city-sized amounts of electricity needed to train AI models. One data center can devour as much electricity as 1,000 Walmart stores, and an AI search can use 10 times the amount of energy as a Google search,” Hiller said.

Hence, they have taken to building their own power generating sources, often gas plants.

The downside to that, as Hansen pointed out, is that the data center developers could still need the reliability of the broader grid. “It’s a balancing act,” he said.

While Hansen in Durango has just started getting inquiries from data center developers, Mark Gabriel, chief executive of Brighton-based United Power, has been fielding inquires for two or three years.

The electrical cooperative covers 900-plus square miles from the foothills of the Rockies to the oil and gas territory of the Wattenberg Field. But it also serves land near DIA as well as along the fast-developing I-76 and I-25 corridors.

As such, United has been getting lots of “tire kickers.” Now, says Gabriel, United actually expects something to come of the talk. Two operators with large load demands have committed to the $650,000 up-front fees, two more are in active negotiations, and several others are talking with United.

“We anticipate at least one to come to fruition,” said Gabriel.

- Kick the (coal) can down the road to 2040? - January 13, 2026

- Pluses and minuses for Colorado’s eastern plains - January 11, 2026

- Rural vs. urban in a panel at History Colorado - January 10, 2026