Trump in 2016 promised to bring back coal jobs. His orders at Craig are best understood as a clumsy effort to do so.

by Allen Best

In October 2016, Donald Trump swung through Colorado, delivering a multitude of promises. “We’re going to put the miners right here in Colorado back to work,” he said during a stop in Grand Junction, presumably referring to coal.

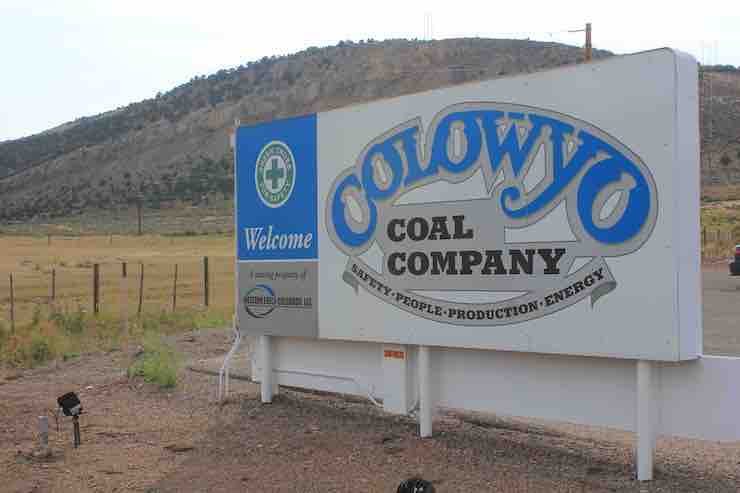

Coal production in Colorado had slid from 40 million tons in 2004 to 12.8 million tons the year Trump visited. Trump failed to deliver. Decline has continued. Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association closed its ColoWyo Mine between Meeker and Craig during October. On Tuesday, 133 workers at the mine were formally laid off.

Tri-State in 2019 made the decision to get out of coal in Colorado. But in 2016, the wholesale provider had agreed to close Unit 1 at the Craig Generating Station by New Year’s Eve 2025.

With barely 24 hours before the scheduled retirement, the federal government interceded. Energy Secretary Chris Wright ordered the 427-megawatt Craig Unit 1 be available for continued operation for another 90 days.

Ironically, Craig unit had then been disabled by mechanical failure for 11 days. Coal plants do break down, some more than others. Problem-plagued Comanche 3, the state’s newest plant, located at Pueblo, went down again in August and will remain so at least until June. Renewables are called intermittent. Coal can be, too.

Tri-State protested the federal order. It provides wholesale power for 15 electrical cooperatives in Colorado’s more rural areas plus others in adjoining states. The cost of the federal order will be absorbed by rural and less-affluent areas, pointed out Duane Highley, the chief executive.

Like other utilities, Tri-State has become comfortable integrating large volumes of far cheaper wind and solar backed by natural gas. Tri-State produces more electricity than it needs to supply its members.

How much will it cost to put the unit back into production? The team of Gov. Jared Polis estimated millions of dollars. Tri-State itself has offered no estimate.

The underlying authority for Wright’s order comes from an executive order issued by Trump earlier in 2025. He cited the 202(c) provision in the Federal Power Act, a 1935 law expanded in 1977. It gives the U.S. government authority to intercede in utilities in special circumstances.

Trump has aggressively expanded what constitutes an emergency. The Craig case illustrates that questionable expansion. Wright, in his order, cited concerns about adequacy of electrical supplies in several Rocky Mountain states. The report Wright cited, North America Electric Reliability Corporation’s 2025-2026 Winter Reliability Assessment, had actually concluded supplies were adequate in coming months, the Sierra Club pointed out.

Democratic politicians in Colorado had a field day. “Ludicrous,” said Polis. Will Toor, director of the Colorado Energy Office, likened it to “Soviet-style central planning, driven by ideology rather than the realities of the electric grid.” U.S. Sen. Michael Bennet called it part of Trump’s “revenge tour.”

The order was best understood as a clumsy attempt to halt the exodus from coal. Coal is on its farewell tour in Colorado. This is a hiccup but not the only one. Colorado Springs Utilities wants to delay closing its coal-burning unit near Fountain. It cites the rising prices of renewables and difficult supply chains.

Supply chains are indeed a problem. That includes natural gas. A new gas plant approved today may take five or more years to complete. And natural gas prices are rising, too.

Xcel Energy a year ago warned of coming problems with resource adequacy. The utility predicted surging demand for electricity from new data centers plus building electrification and EVs. How real will this demand from data centers be? Hard to say. Some think we have an artificial AI investment bubble that might burst in 2026. We’ll see.

Clearly, though, demand for electricity has accelerated after a decade of slow growth. The United States faces an energy crunch of historic proportions, said Brian Deese, a former energy aide to President Barack Obama, and Lisa Hansmann in a recent essay published in Foreign Affairs, a journal.

RMI, the think tank based in Basalt and Boulder, on Jan. 6 noted that utilities can still do more to tap “soft path” solutions that founder Amory Lovins described in his famous 1976 “Road Not Taken” essay in Foreign Affairs.

Ron Sinton, who operates Sinton Instruments, a company in Boulder, believes we can better pair our electrical demands with renewable generation. EVs, for example, can be charged at mid-day when we often have a glut of solar power.

Keeping the coal plant open in Craig was a simple and likely expensive solution that leaves open the question of who will pay? The better solutions will likely be more complex but less costly to ratepayers.

- Colorado tops 6 million - January 28, 2026

- Difficult decisions on Colorado’s eastern plains - January 26, 2026

- Xcel can fix downed coal unit at Pueblo but at what cost? - January 22, 2026

I made a three trips to the ColoWyo mine area over the past year. Not the mine itself but the YUGE BEAUTIFUL SOLAR FARM built on land leased from them. The Axial Basin Project connected to the grid in October and at145 MW AC it’s the 7th largest solar farm in CO and the largest on the West Slope. Right under the powerlines between Craig and Rifle. For some reason, no press release has been issued, and it never seems to get mentioned. I kept trying to get a good pic from Duffy Mtn, N of it and S of the Yampa River. From that vantage point one could see the old coal mine’s load out for the train to Craig in back of one of the new PV arrays. But glare, smoke or haze always seemed to interfere. I did encounter some antelope who seemed more disturbed by my car stereo than the fencing and construction.

The variable output from solar and wind needs variable generation for backup. If the coal plants could provide that I wouldn’t mind if they continued to operate longer. But they are inflexible with high minimum turndowns and take forever to raise steam from a cold start. (Modifications can improve these, but seems like that ship has sailed.)

Anyone who has an EV or even electric DHW or a dryer can attempt to run them when the grid is more flooded with renewables using the website Sinton has created. https://www.sintoninstruments.com/news/

Hopefully all EV owners know they can save money and the grid and CO2 by avoiding evening peak demand hours. Even w/o getting on TOU rates, Xcel provides a rebate for programming your car or charger. (Linking our Kia and the Xcel service was a tad “interesting” but ultimately successful. Good job for teenager.) Other programs from other utilities. For my water heater I have an Aquanta controller which is a DIY installation and app to keep it off during morning and evening peaks.