Negotiations a century ago divided the river into two basins. That created problems. Why not scrap the artifice of two basins?

by George Sibley

Hard times in the Colorado River region continue. A near-average snowpack dissipated into a 40% flow into Powell Reservoir. Dry soils in the warming world accompanied by increased evaporation and plant transpiration are taking big gulps. The annual 24-month projection from the Bureau of Reclamation indicates that another similar year could drop Powell Reservoir levels to the point where both hydropower production and full Compact deliveries to the Lower Basin could become impossible by November 2026.

Negotiators for the seven basin states who have been trying to work out a river management plan to replace the failing current management strategies, with the basin’s 30 Indian nations and Mexico looking over their shoulders, remain in a stalemate. Trump’s Interior Department officials have given them until mid-November to negotiate a draft plan for operations beyond 2026.

The crisis at hand, however, delivers an opportunity to achieve what the representatives of the seven states wanted when they convened in Washington in January 1922 to create a Colorado River Compact: they wanted a seven-way division of the consumptive use of the river’s waters that would transcend on the interstate level the appropriation doctrine all seven states adhered to intrastate.

Six of the state representatives feared that southern California, the seventh state, was growing so fast and already using much of the river’s water, that they could lose out entirely in a seven-state horse race to appropriate the water. The representatives all accepted the first-come, first-served appropriation law as holy writ within their states but saw its limits when looking at the whole river and the regional challenge of uneven development.

California only met with the other six states because it needed the federal government to build a big dam to prevent the annual uncontrolled flood of snowmelt being “wasted” to the ocean, and California knew that Congress would provide for that big dam only if all seven states were assured they would have a share of the water once the river was controlled.

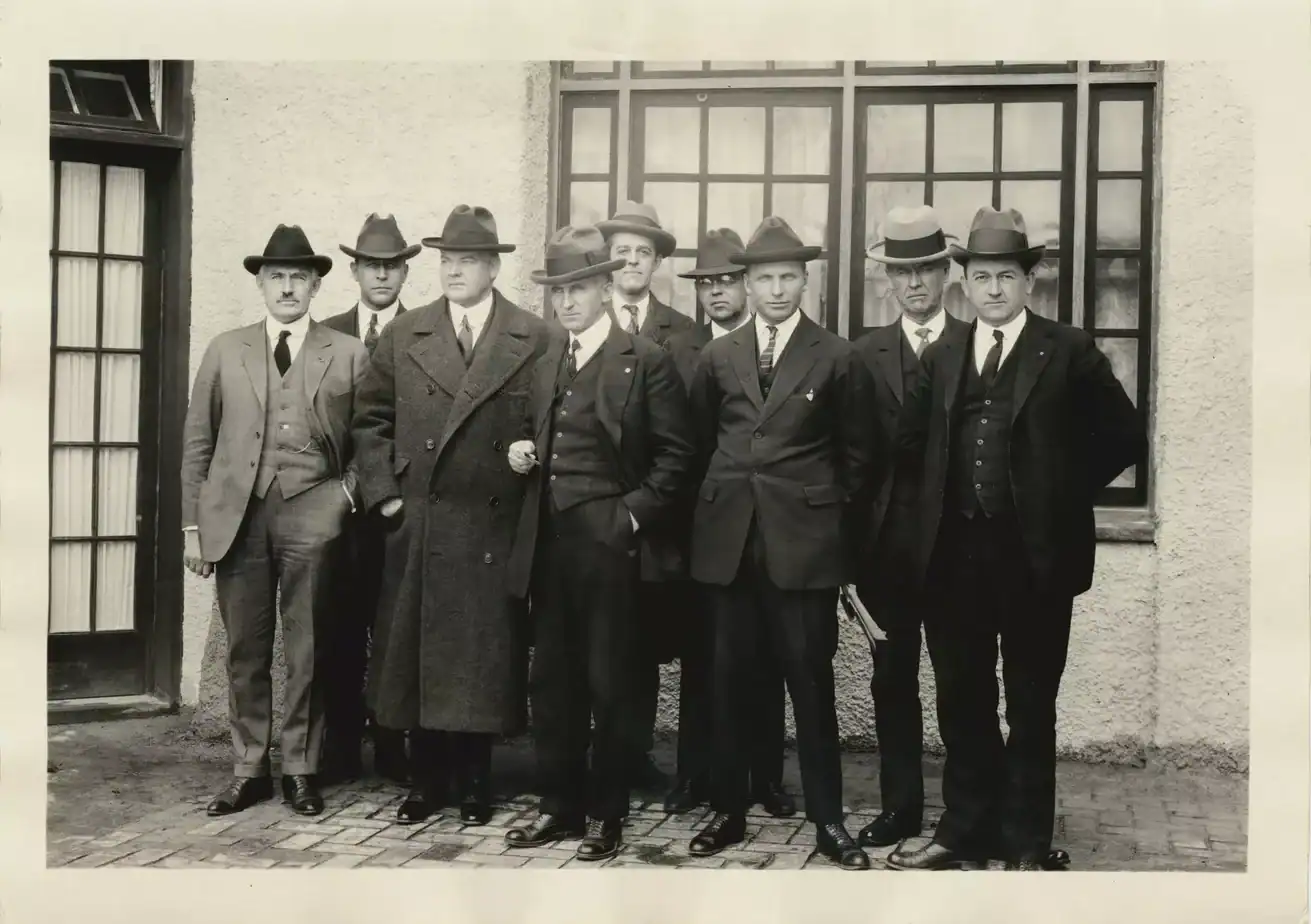

In negotiations overseen by Herbert Hoover, third from left, representatives from the seven basin states gathered at a resort near Santa Fe in 1922. Photo/Colroado State University Library.

After several days of trying to work out an equitable seven-way division, frustrated compact negotiators gave up on that idea. Each negotiator had come with estimates of his state’s future water needs based on potentially arable land, mining-generated industry, and urban development. Their rosy projections for water needs added up to half again the Bureau of Reclamation’s rosiest estimates of Colorado River flows. No negotiator wanted to take home a plan that diminished his state’s envisioned futures.

Several negotiators thought they should abandon the whole idea of an interstate compact. Herbert Hoover, the commission’s federal representative and chairman, himself an engineer eager to see the big dam built, persuaded them to stay with the idea through 1922. But they did not meet again for serious planning until November, after Hoover and Delph Carpenter, Colorado’s representative to the commission, circulated the idea of a two-basin division to break the impasse over the seven-way division. Hoover was able to convene a November charrette to work until a compact was done.

Toward the end of an 11-day marathon at a resort near Santa Fe, with 18 transcribed sessions and who knows how many informal barroom and hotel room caucuses, Hoover summarized their situation:

We finally reached, in effect, this general conclusion as to the form of the compact, and that was that none of the figures and data in our possession, or within the possibility of possession at this time were sufficient upon which we could make an equitable division of the waters of the Colorado River [in perpetuity] ….

[W]e make now, for lack of a better word, a temporary equitable division, reserving a certain portion of the flow of the river to the hands of those men who may come after us, possessed of a far greater fund of information; that they can make a further division of the river at such a time, and in the meantime we shall take such means at this moment to protect the rights of either basin as will assure the continued development of the river. (Text from the 12th of 18 transcribed November meetings, boldface added)

No one – with the probable exception of Delph Carpenter – was very happy with the “temporary equitable division” the commissioners took home to their states. Arizona’s legislature refused to ratify it, and it took several years to get it through the other six state legislatures.

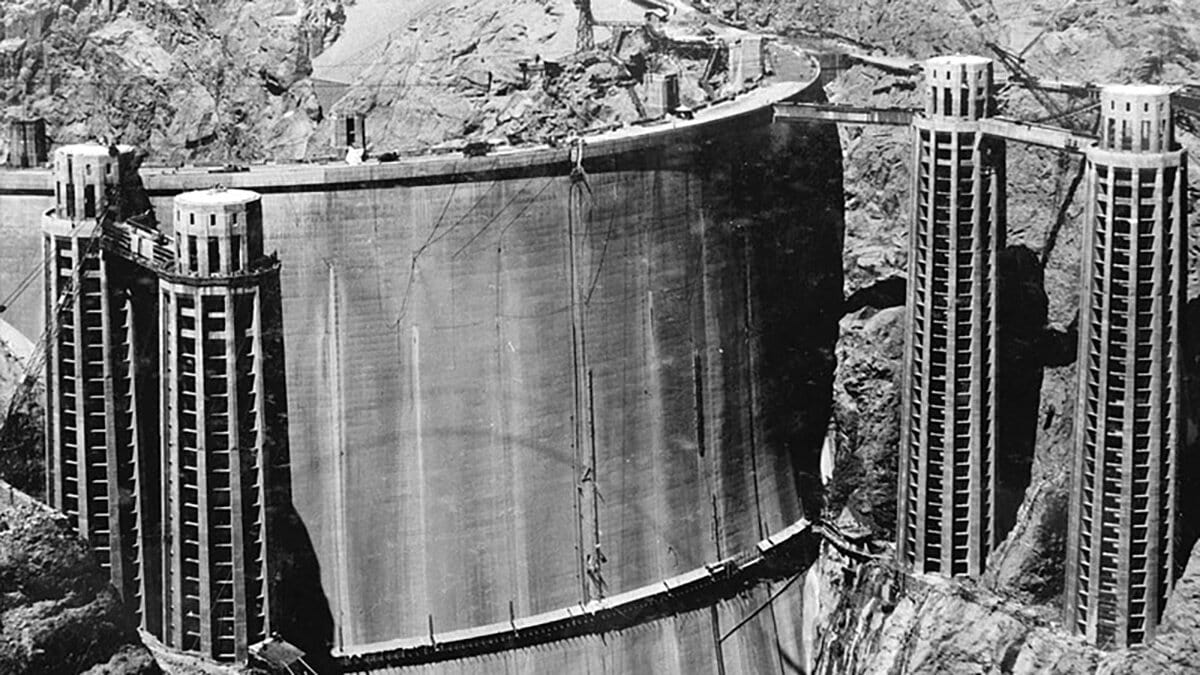

However, the U.S. Congress was somewhat eager to develop the river, making the desert lands available for development, and decided that having six of the seven states on board was good enough. The Boulder Canyon Project Act was passed in 1928, and Hoover — who by then had become president — was able to launch construction of not just the big dam later named for him, but also Parker Dam (the holding bay for the Metropolitan Water District’s 250-mile aqueduct to Los Angeles), and the Imperial Dam and All-American Canal which deliver water to the giant farms in the Imperial and Coachella valleys. This regional development set the course for the 20th century’s public funding of public projects executed by private enterprises.

Subsequent regional development in the Upper Basin states achieved the compact’s stated goal to “secure the expeditious agricultural and industrial development of the Colorado River Basin,” as stated in its preamble (Article I). In fact, even before the completion of the Colorado River Storage Project and the Central Arizona Project, the river was described as “over-appropriated” – more water “developed” than the river actually carried.

A century later, however, we know that the Compact’s “temporary equitable division” has not achieved most of the other goals listed in the preamble. It did not “provide for the equitable division and apportionment of the use of the waters” in either the division between basins specified in Article III(a) nor in the relationship between the two basins stated in Article III(d).

The two-basin division also obviously did not “promote interstate comity” nor “remove causes of present and future controversies.” If anything, the compact created controversies with badly written sections like Article III(c) on the Mexican obligation, and Article III(d) on inter-basin “obligations.” (If you want to review the Compact, you can find it here.)

The Boulder Canyon Project Act of 1928 authorized construction of what later was named Hoover Dam and apportioned Colorado River water among the Lower Basin states: Arizona (2.8 million acre-feet); California (4.4 million acre-feet ); and Nevada (300,000 acre-feet).

What had been achieved, however, was what the Compact commissioners had wanted to do in 1922: a century of development had divided the consumptive use of the river among the seven states and Mexico. Allotments for the three lower basin states were set by the Boulder Canyon Project Act in 1929 as acre-foot portions of the Compact allotment of 7.5 million acre-feet, and confirmed by the Supreme Court in its 1963-4 Arizona v. California decision. Mexico received its share, 1.5 maf, in a 1944 treaty negotiated through the U.S. State Department.

The four Upper Basin states negotiated a compact for their share of the river in 1948. But by then, the river flows were known to be variable, and usually less than the Compact’s allotment for each basin and Mexico. Fully aware of this, the Upper Basin states divided their fluctuating share by percentages.

The “federal reserved rights” for the Basin’s 30 Indian nations — barely given a placeholder in the 1922 Compact — have been shoe-horned in as state responsibilities through the 1952 McCarran Amendment to a resource bill, which says that all federal reserved water rights, for all public lands as well as the Indian reservations, have to be adjudicated in the state water courts. This is happening, slowly and often painfully, but it is another and lengthy story.

River flows through the development era from 1930 to 2000 averaged around 14.6 million acre-feet. Upper Basin use fluctuated around 4.0 million acre-feet. Proportionally, the upper basin used about one-third of the annual flow, the other two-thirds went to the Lower Basin and Mexico – including system losses unaccounted for.

The alarming draw-down of the river’s major reservoirs since 2000 has been only partially caused by “drought” and permanent climatic aridification. The bulk of the draw-down has been due to a “structural deficit,” resulting from the Compact’s failure to allot responsibility for natural “system losses” compounded by the development of large water projects – evaporation, plant transpiration, bank storage, etc. System losses for the developed river are probably 13-14 percent of the water flowing from the headwaters snowpack – growing as the world grows warmer and drier.

Lower basin states have blithely refused to incorporate their “system losses” as well as their portion of the Mexican share into their allotments. They have instead let the amenable Bureau of Reclamation release those losses as “surplus” from Powell and Mead storage. But no real surplus has existed since the Central Arizona Project began to taking water after 1985, along with increased upper basin uses (still well below its “compact allotment”).

Good news from the current negotiations is that the lower basin states have agreed to absorb that “structural deficit” and their share of the Mexican obligation into their allotments of the river. Upper basin users have already been doing this.

Dividing the river’s waters among the seven states and Mexico was impossible to do in 1922. By 2022 it was largely accomplished – like it or not. The “temporary equitable division” into two basins (which wasn’t really that equitable) is now just getting in the way; eliminating it would unload quite a lot of unnecessary baggage. We would be much closer to thinking of the Colorado as one river with one set of challenges for everyone, rather than this “Cold War” between two basins.

Now the big challenge lies in fitting that accomplished division of the 14.6 million acre-foot river of the 20th century with the 21st century river of today, whose flows since 2000 have averaged ~12.5 million acre-feet – dropping as the world warms.

In a fair, just and moral universe, we could use basic high school math to create management guidelines for the river. If a state’s allotment (including a proportionate share of system losses) of a 14.6 maf river is X percent, what will be that state’s new allotment if the river’s volume drops to 12.5 million acre-feet? Or to 11.5 by 2050? Do that for all users and, presto, there’s everyone’s new 21st-century allotment, learn how to live with it –

One can already hear the harrumphing from California’s Imperial Valley. What about our senior water rights? If you think we’re going to take the same cuts as everyone else, we’ll see you in court!

Scott Cameron, the Interior Department’s acting assistant secretary for water and science, actually spoke to that eventuality in a water meeting in Arizona: “Having senior water rights is a wonderful thing, but having senior water rights does not give you a free pass to ignore what’s happening in the greater community.”

What’s happening in the greater community is diminishing flows for everyone due to a warming climate that is everyone’s and no one’s fault. That’s a problem of a different order of magnitude from the user conflicts the senior-junior appropriation doctrine developed to resolve.

If Cameron’s observation (unusually perceptive from the Trump administration) were to prevail in federal policy, it might facilitate the serious discussion that is needed about the extent of appropriation law in the arid West. Westerners who convened to create the 1922 compact wanted to suspend the appropriation doctrine between the states for a good reason: the uneven pace of regional development. Now we have a diminishing river caused by everyone, seniors and juniors alike – an even better reason for transcending the one-size-fits-all appropriation doctrine.

We get news every day about the fairness and morality of our small sector of the universe. Pray for rain; it’s more likely.

- Romancing the River: Dancing With Deadpool - December 28, 2025

- Why not create the Colorado River Compact they wanted in 1922? - September 1, 2025

- Dick Bratton and ‘A River Once More’ - March 5, 2025