Electrical cooperative through August had achieved 87% clean energy for the year

by Allen Best

Over the years, I’ve noticed a pattern with Holy Cross Energy. Since Bryan Hannegan took over as general manager in 2017, the electrical cooperative has been shy about making premature bold and ambitious claims.

Oh, it has set goals. But it does so somewhat cautiously.

Ten to 15 years ago, many municipalities were adopting the aspirational greenhouse gas reduction goals without any idea of how to get there. Sort of like a New Year’s resolution about losing weight without bothering to check out the gym schedule. Or, more currently, a meme on Facebook that you pass along without original thought.

Holy Cross took its time in adopting its goal. When it did so several years ago, it was a little bit like announcing plans to climb Everest. It said it wanted to be 100% renewable energy by 2030. It now looks in comfortable position to achieve 87% for 2025.

That’s not bad for an electrical cooperative that owns 8% of Colorado’s largest coal plant, Comanche 3. In January 2019, however, it announced a deal with Guzman Energy. Guzman takes the power and sells to its various customers in Colorado and elsewhere. Holy Cross remains a part-owner of Comanche but it can secure its power elsewhere.

Screenshot

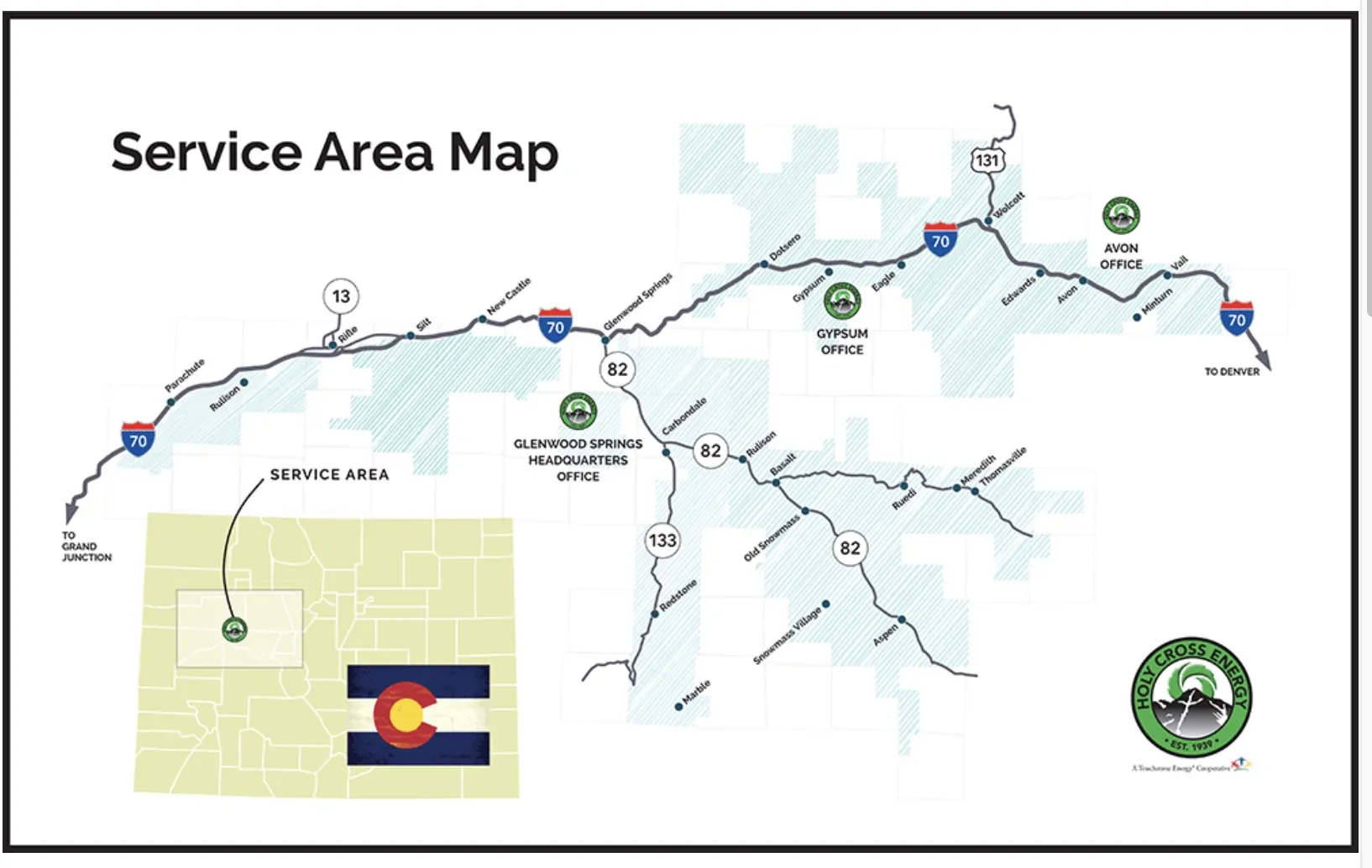

The Glenwood Springs-based cooperative has invested in local solar-and-battery projects in the Vail-Aspen-Battlement Mesa triangle, where it has 43,500 members and delivers electricity to 60,000 meters.

Most of these projects have been 10 megawatts of solar generation coupled with battery storage of 20 megawatt-hours. One such project is in the Parachute area, another south of Silt in the Mamm Creek Valley. It also has some hydro, including from a project at Palisade, on the Colorado River.

The larger story lies hundreds of miles away. Because of an agreement reached with Xcel Energy in the early 1990s, Holy Cross Energy can use Xcel’s transmission capacity at relatively low cost.

This has allowed it to access 30 megawatts of solar capacity from a project southeast of Denver called Hunter Solar. Most significant are the 72 wind turbines of the Bronco Plains Wind II project near Seibert, about 130 miles southeast of Denver. During winter months, when Holy Cross has its greatest demand, it gets 150 megawatts of production. During summer, it gets 100 megawatts.

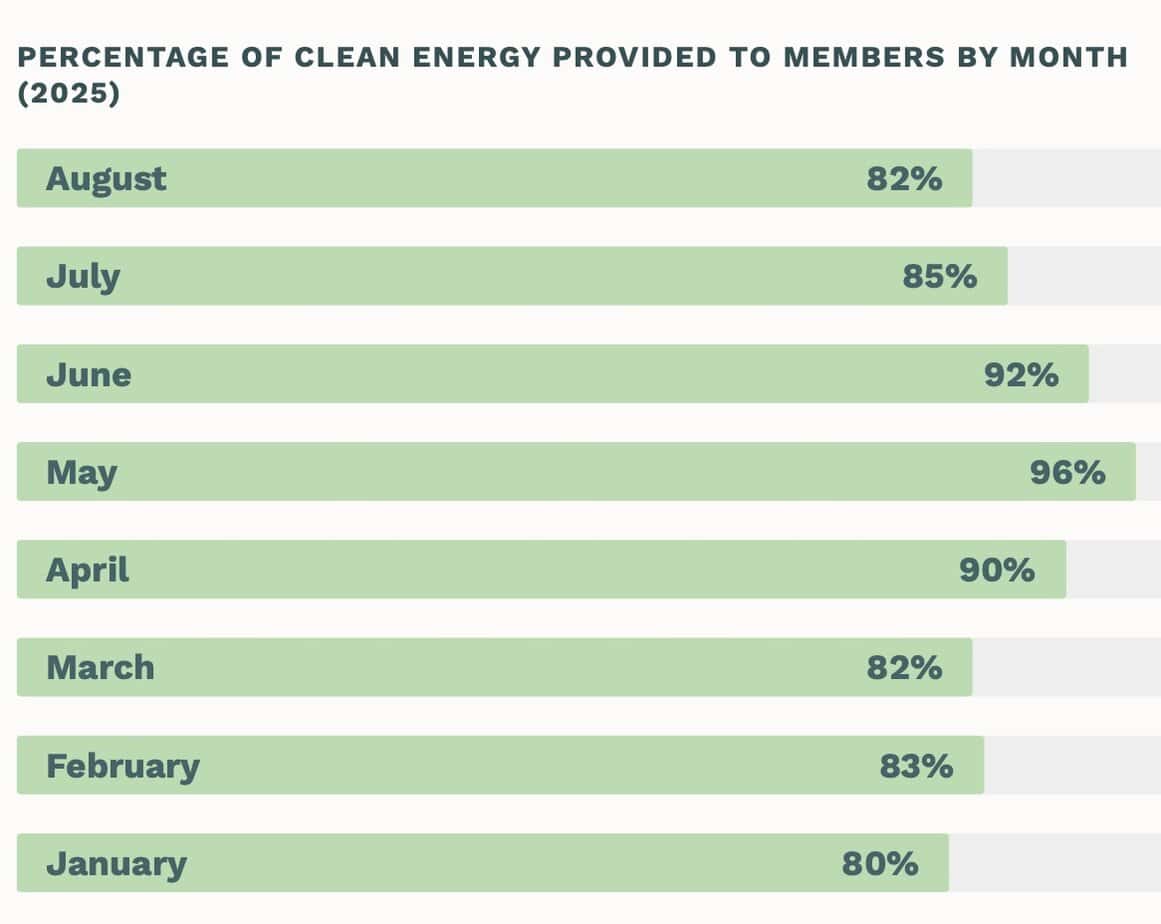

In September 2024, when Holy Cross gained access to this wind capacity, it surpassed 90% clean energy on its system. The cooperative warned that this percentage would sag during winter, when Aspen and Vail and their sibling resorts get busy and demands surge. That proved true. The percentage dropped to 68% in December.

In January, it hit 80% and hit a high of 96% in May. Recently, Hannegan, in a post on LinkedIn, announced that Holy Cross had surpassed 80% for eight consecutive months. It is now 87% for the year. With the windy months of autumn upon us, that puts Holy Cross in a very good place to achieve its goal of 85% for 2025.

Screenshot

This is actually somewhat behind where it hoped to be in 2023. Then, in its “Power Supply Roadmap,” it said it expected to achieve 90% renewable power supply by the end of 2024 on an annual basis.

Transmission seems to have held Holy Cross back. It now hopes to achieve 90% in 2026 but has cautioned it may not succeed until 2027. Success seems to depend upon the progress of Xcel Energy in completing the Colorado Power Pathway, its 550-mile transmission loop around the state’s eastern plains. The 345-kV transmission line has five segments. Two segments have been completed.

The 2025 strategic plan was more restrained in its articulation of goals. More prominent was mention of the need for storage. Storage, it said, will “play an increasingly significant role, both as large grid-tied resources and as smaller distributed resources.”

Meanwhile, it has issued a request for proposals. One round of solicitations closed July 1. Holy Cross has not announced what proposals, if any, it has chosen from those bidding projects.

A new solicitation, for 60 megawatts, is specifically oriented toward the day when power from Comanche 3 is no longer available. One criterion is whether the generation will be available from December through February.

Why does Holy Cross need power to replace the 60 megawatts from Comanche 3 if it no longer gets that coal-fired generation? I reached out directly to Holy Cross for an answer.

“We want to maintain the rights to the same level of capacity moving forward, even after the plant closes,” explained Sam Whelan, the vice president for finance at Holy Cross.

This goes back to a 2021 agreement at the PUC which stipulated that Holy Cross will have “in its sole discretion” the option to select one or more replacement resources owned by or contracted to Holy Cross and interconnected with the Xcel transmission system.

This gives Holy Cross the authority to pick from among the bids to Xcel Energy as part of its just transition solicitation. That process began a few weeks ago and is intended to hurry the process of getting projects started by July 2026 in order to take full advantage of federal tax credits being phased out by the One Big Beautiful Act. (For background: “Will Trump try to keep the coal burning in Pueblo?” Sept. 3, 2025, Big Pivots.

Hannegan several times during his years at Holy Cross said that part of the ability of the cooperative to achieve deep gains depends upon an agreement struck decades ago that allows Holy Cross to piggyback on Xcel’s transition network.

I believe I first interviewed Hannegan in 2018. He had previously worked at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, but his resume also included seven years at the Electric Power Research Institute in Palo Alto and a stint in the administration of George W. Bush. He said that achieving 85% to 90% clean energy would be relatively easy. The final 10% to 15% would be far more difficult and likely more expensive.

Holy Cross Energy has added solar and storage projects at various locations in its service territory, including this project near the Colorado Mountain College central campus near Glenwood Springs. Photo/Allen Best

So far, Holy Cross has been able to maintain some of the cheapest electricity rates in Colorado, 11 cents/ kWh, Hannegan said in his LinkedIn post. That’s ironic, of course, given the affluent markets that comprise part of its service territory.

Absent in this narrative has been any mention of the more nuanced programs of Holy Cross. Through incentives it has encouraged placement of batteries within homes and business. Demand-side management is another component. If a utility can shave the peaks of electrical demand, it can lessen the need to draw on fossil fuel resources or more expensive infrastructure to deliver renewables. That is a very big story.

What else will be needed for Holy Cross to achieve its 2030 goal? The last time I heard Hannegan talk, he mentioned getting close to 100%, not hitting the target. In late 2023, at a Vail Symposium event, he said some natural gas will remain in Colorado’s electric system even in 2050.

Hannegan has also been careful to distinguish between the difficulty of a relatively smaller electrical cooperative achieving 100% and that of a giant investor-owned utility like Xcel with its 1.6 million customers. That may also explain why Aspen Electric, which serves about two-thirds of Aspen, a far smaller area than Holy Cross, was able to achieve 100% emissions-free electricity in 2015.

What is realistic for 100% goals now? The slope seems to have steepened during the last two years as demand from data centers has escalated.

A conference in Breckenridge on Wednesday, Oct. 8, will have Hannegan on a panel to discuss that question. The Mountain Towns 2030 session will also include:

- Chris Hansen, chief executive of another electrical cooperative, Durango-based La Plata Electric,

- Duane Highley, CEO of Tri-State Generation and Transmission; and

- Andrew Holder, Xcel Energy’s director of community relations and local government affairs.

- Jon Creyts, the chief executive of RMI, will moderate.

I must admit to some partiality to this panel in that the seed for this was an interview I conducted with Hansen last November, after he had resigned from the Colorado Senate to take the position in Durango. I only wish it were an hour-long panel session, not 30 minutes!

- Holy Cross Energy on track to achieve its 2025 goal - October 1, 2025

- These ‘Traveling Wilburys’ of the Colorado River are being heard - September 28, 2025

- Xcel to pay $640 in Marshall Fire settlement - September 24, 2025

IMHO, as we get to high renewable fractions for these small segments of demand, we need to switch from annual net to hourly accounting for renewables vs. fossil use. Without a lot more storage/batteries, they are at times trading away wind or solar, and at other times buying fossil fuel power over the grid. Colorado as a whole is now at 50% renewables, with only a modest amount of trading outside the state due to transmission constraints. So I sort of look at all the electrical supply in the state as close to this. That’s getting pretty good. NM is at 70% (30% solar, 40% wind). Nice. And with higher kWh/capita, but with more trading to the west, and more to come via SunZia.

In any case, the part of town served by HCE is pretty happy with them. And even Xcel deserves some credit for getting to 50% renewables and keeping rates at or below the national average.

P.S. Fractions are % of in-state generation, not consumption, from Q3 2024 through Q2 2025 from EIA.

Just love your insights, Fred. Keep them coming!