Powell was both an adventurer and a scientist. Perhaps that’s exactly what we need now to end the Colorado River stalemate.

by George Sibley

The recent Big Storm dropped maybe a foot of snow in the headwaters of the Colorado River. That was on top of next to nothing in most places after two mostly warm dry months. We need a Miracle March or Amazing May to get us close to what we once called a normal runoff.

Meanwhile, negotiations among the seven states in the two contending basins created by the Colorado River Compact continue to come up with next to nothing for a post-2026 management plan. That compact was built for a different river than we have today, and a new governance is needed. The increasingly ominous and relentless changes in the climate provide the backdrop of these seemingly futile discussions.

As with the changes we know will be needed for our climate, we seem incapable of the kinds of personal and cultural changes and growth needed to resolve our Colorado River challenges. How else to explain all the supposed adults in the Colorado River Basin room sitting across the table from each other for two years and accusing each other of being the problem?

What would John Wesley Powell do were he here today?

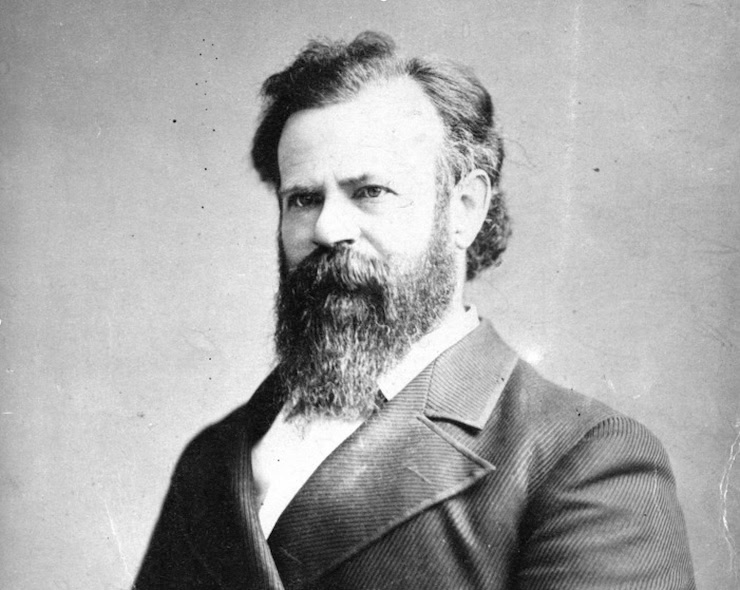

Most of us know Powell as a 19th century romantic figure, the adventurer who was the first to go down the canyons of the Colorado, a scientific trip that turned into an epic of survival. There was another Powell, the scientist who helped create the U.S. Geological Survey. As its director through the 1880s, he instilled the scientific discipline even today that makes it one of the most trusted federal agencies.

Which was he, the romantic adventurer or the disciplined scientist? The civilized mind likes neat categories. I would argue that this “adventurer-scientist” might be a model for getting us through our current troubles – or at least more honestly engaging in them.

The son of a mostly impoverished circuit-riding Methodist preacher, Powell was reared in upstate New York, Ohio and Illinois. On those “family farms” he absorbed the compelling but naively conceived Jeffersonian-agrarian vision of a nation whose foundation would be decentralized and mostly self-sufficient communities of farm families. This vision did not blind him to the poverty that came with too little community cooperation among Jefferson’s beloved “rugged American individualists.”

Powell, despite his innate curiosity, essential for both the adventurer and the scientist, never got “credentialed” as a scientist. He studied science at two colleges but never completed work for a degree, probably because he spent more of his time through the 1850s adventuring. One year he rowed from Pittsburgh down the Ohio River to its confluence with the Mississippi. Another year he rowed the length of the Mississippi. Still another year he walked across the new state of Wisconsin.

A dedicated abolitionist, he joined an Illinois volunteer brigade for the Civil War and became an officer in an artillery company. His right arm below the joint was shattered by a bullet and amputated, but it did not slow him. He healed and returned to his unit to finish the war.

After the war, despite his own lack of a college degree, he taught geology at Illinois Wesleyan University. During his summers he traveled to the West. Here, he saw the unsuitability of the naively conceived one-size-fits-all Homestead Act in the arid and semiarid lands. He also saw the willy-nilly and often corrupt process of both western agrarian settlement and industrial development. And he observed what the more organized Mormons were doing with irrigated agriculture in the Utah Territory. There, they worked as organized communities rather than Jefferson’s beloved “rugged American individualists.”

Powell had ideas about the settlement of the arid West, things to say, but he was basically just a teacher from “back east” who spent his summers adventuring. How could he get a hearing for his concerns and ideas? He needed some way to gain public attention.

Frederick Dellenbaugh accompanied Powell on the second expedition. Here he is seen along the Green River in Lodore Canyon in May 1871. Top photo: John Wesley Powell in 1874, when he was 40. Photos/National Park Service

To do that, he turned his destiny over to his romantic adventurer side. He would do a scientific investigation into one of the remaining blank spots on the continental map, the region beginning where the Green and Grand rivers (now the Colorado) that drained the western slopes of the Southern Rockies disappeared into a maze of canyons.

Wallace Stegner, in Beyond the Hundredth Meridian, his great book about Powell and the development of the arid lands, credited Powell’s scientific grounding with getting him through his 1869 expedition in the canyons. “Though some river rats will disagree with me,” said Stegner, “I have been able to conclude only that Powell’s party in 1869 survived by the exercise of observation, caution, intelligence, skill, planning – in a word, Science.”

I disagree with Stegner on that point. The advance planning for the trip sank in the first set of Green River rapids. One of the wrecked boats contained a large portion of both their food supply and scientific instruments. They basically had no idea what they were planning for. They gradually acquired some skill at negotiating rapids (and knowing when to portage instead), but they started with no skill and paid the price. Observation was limited to the stretch of river before the next bend.

Frederick Dellenbaugh, who accompanied Powell as a teenager on Powell’s second trip into the canyons in 1871-73, became an adventurer-explorer in his own right. He wrote a book, The Romance of the Colorado River, which was mostly about Powell’s two canyon trips. Dellenbaugh asked his “mentor” what he would have done had he come to a Niagara-scale waterfall with sheer walls, no room for portage, and no way back upriver.

“I don’t know,” Powell answered. Scientific caution was not a factor in this second trip either. They leaped before looking because there was no way to look first.

Stegner to the contrary, I would argue they survived the way adventurers survive (except when they don’t): a kind of adaptive intelligence, for sure, figuring out how to make rotten bacon and moldy flour edible, how to fabricate replacement oars, how to deal with the unexpected quickly and decisively.

Mostly they survived by gutting it out, keeping spirits from crashing completely with routines and morbid humor: Powell getting out the remaining instruments, rain or shine, to take their bearings (and getting spread-eagled on cliffs requiring four limbs rather than three), just getting back in the boats every morning and again turning their lives over to the unpredictable will of the river.

It worked out. Ninety-one days after starting, they made national headlines when they floated half-starved into a town near the river’s confluence with the Virgin River. And Powell, a national hero after that, procured a government job doing a “survey” of the Utah territory.

At that point, Powell the scientist took over. His belief in the agrarian vision, the counterrevolution to the Industrial Revolution, shaped his scientific work. The unstated purpose of the western surveys by the 1870s was to map out potential resources for the fast-growing industrial empire of the United States.

Powell covered those bases, but the heart of his “Report on the Lands of the Arid Region” in 1878 was an analysis of the potential of the arid lands for fulfilling the romantic agrarian vision for America. He made a strong case for replacing the Homestead Act’s one-size-fits-all 160-acre homestead allotments with two alternatives for the arid lands:

1) 80-acre allotments for intensive irrigated farming, that being as much as a farm family (pre-tractor) could successfully tend; or

2) “Pasturage” allotments of 2,560 acres on lands mostly unsuited for irrigation. Four full sections for stockgrowers with up to 20 irrigable acres for growing some winter hay and the ubiquitous kitchen garden.

Powell went even further in that report, waving a red cape in the face of the agrarian movement’s commitment to Jefferson’s “yeoman,” the “rugged American individualist.” Settlement, he said, should not be done on a willy-nilly “first-come-first-served” basis. Instead, each watershed should be developed by an organized ditch society working cooperatively from a plan assuring that every member got a fair allotment of water and that the water was most efficiently distributed.

This had been foundational to the communal land-grant system imported from Spain to Mexico by those who called the West El Norte. It was also understood by many of the native peoples already in the Americas: the un-American notion that it takes a village and a stream to raise good crops in the arid lands.

And the right to use that water should be bound to the land, he said. No individual water rights that could be bought and sold without the land.

Powell’s report even included model bills for state and federal legislation. He was thoroughly ignored because everything that he suggested was contrary to the romantic mythology of the Winning of the West — Jefferson’s legendary yeoman conquering the wilderness, the rugged American individualist going forth with rifle, ax and Bible to advance Christian civilization.

That American mythology from the start was always “all radiant with the color of romance,” in the words of desert poet Mary Austin, with very little attention to the facts of nature. That is the primary reason two out of three homesteads failed as settlement moved into the semi-arid High Plains and the arid interior West.

Powell’s only partial success was to be convincing that “rain would not follow the plow” and that the agrarian movement would have to learn how to irrigate in the arid West. Even that victory was kind of turned on its head by the myth-makers. An irrigation movement during the last decades of the 19th century to “make the desert bloom” like the Biblical rose – the whole desert! A series of almost religious Irrigation Congresses grew through the 1890s that culminated in the creation of the federal Reclamation Service in 1902. Powell appeared at a gathering in Los Angeles during 1893 to remind irrigation’s proponents that there was only enough water to irrigate around 3% of the arid lands. He was booed off the stage.

Undeterred, Powell kept on pushing. He was “present at the creation” of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in 1879 and two years later became director. In that capacity he tried to keep both the Agrarian Romance and the iron facts of aridity front and center.

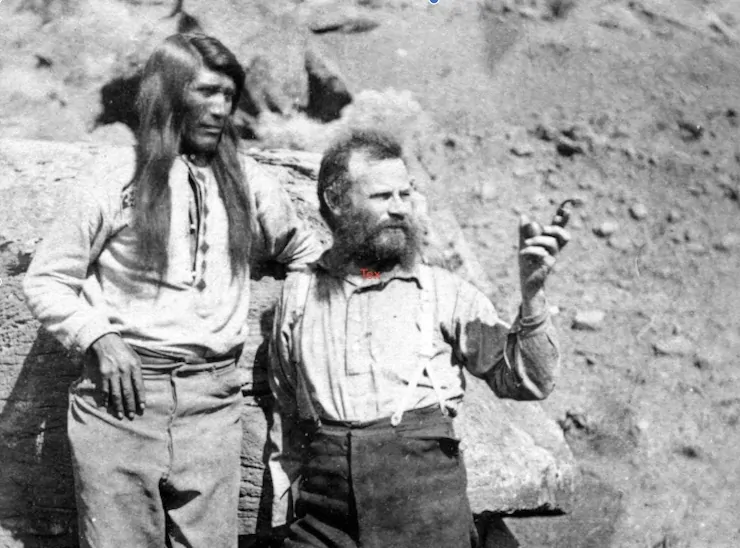

Au-Gu, chief of the Paiutes, and Powell overlook the Virgin River in 1873. Photo/National Park Service

Powell’s biggest push was an attempt to pause land settlement entirely while the USGS completed mapping water resources and adjacent irrigable areas of the interior West. He was just a vote or two in Congress from a moratorium on new homesteads process until the study was done. But once some of the senators fronting for the industrialists realized what he was doing, they shut him down — and with a vengeance. He realized that to save the USGS, he had to divorce himself from it. He resigned in 1894. (Western extractive industries depended to some extent on failed homesteaders for their labor supply.)

Powell was not out of work, however. From his pre-canyon days he had been interested in the First Peoples of the West. Most Euro-Americans saw the natives, at best, as raw material for assimilation to Christian industrial civilization, and at worst, as vermin to be wiped off the land. Powell instead saw them as people who had survived and even thrived in the region with Stone Age technology and therefore people from whom something might be learned.

His efforts to communicate with those he encountered in his Utah survey led to the 1877 publication of a book, Introduction to Indian Languages. It led, two years later, to the creation of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology in the Smithsonian Institute with Powell as director, a position he held until his death in 1902. Creation of the bureau resulted in the first comprehensive linguistic survey of indigenous tongues, Indian Linguistic Families of America, North of Mexico (1891).

Some of his recommended policies did reflect the unconscious arrogance of his times: he believed his task was to help the First Peoples along the path to becoming civilized, and one way to help that happen was to remove them from their homelands. The process was well underway by then anyway, but certainly was not Powell’s best idea.

Major John Wesley Powell, in both ethnology and in creating the USGS, established a high standard for government science. He insisted upon attention to the facts while still trying to carry forward what Bruce Springsteen called “the country we carry in our hearts” in this ever-evolving, devolving, careening, diverted, perverted, and currently severely damaged Romance of the American Dream. It is still as contested today as it was in Powell’s day and in Jefferson’s day.

What would Powell do, if he were here today, sitting in on the stalemated negotiation process? He could be forgiven if the first thing he said — if they even gave him the floor for a moment — was “I told you so.” But he probably wouldn’t say that.

Instead, in my imagination, I could see him saying something like:

“Let’s do an exercise. Start by throwing out everything you have done based on the river you thought you had. Then start again with the river you know you have now. Acknowledge the fact that you don’t need to worry any more about dividing the waters among your geographically ridiculous states, because you have already divvied up more than is in the river you have now. That task which you couldn’t do a century ago is now overdone. Then start thinking about how you can put the divided river back together. Then go adventuring, with good science at your side.”

Maybe something like that. All I imagine is that it would be interesting.

I leave you with a Colorado River image of Powell, related in Dellenbaugh’s Romance of the Colorado River. There were afternoons in that second voyage into the canyons, in the placid stretches between rapids, when the men would rope the boats together, and Major Powell — the man who had shown that the rivers above the canyons and the river below the canyon were one and the same river — would sit in his chair on the deck of the Emma Dean and read to them from the romantic adventure stories of Sir Walter Scott.

Turning problems to be avoided into challenges to be embraced – it’s all in the adventure.

George Sibley writes in Gunnison, at the headwaters of the Colorado River. This essay is adapted from a blog posted at sibleysrivers.com.

- What would John Wesley Powell say today? - January 31, 2026

- Romancing the River: Dancing With Deadpool - December 28, 2025

- Why not create the Colorado River Compact they wanted in 1922? - September 1, 2025