Snowpack realities must be recognized by all seven Colorado River Basin states, says Becky Mitchell, Colorado’s chief negotiator

by Allen Best

Becky Mitchell was particularly busy during the last week of January. On Wednesday, Jan. 28, she opened the annual Colorado Water Congress conference with a 1,100-word speech (the prepared remarks are below) that reiterated Colorado’s position in the stalemated Colorado River discussions.

Lower-basin states, said Mitchell, Colorado’s chief negotiator in Colorado River affairs, must fully come to terms with the changed realities on the Colorado River. “This means releases from Lake Powell must reflect actual inflows, not political pressure,” she said. “If reductions aren’t real, reservoirs won’t recover.”

The next day, Mitchell was in Washington D.C. along with Colorado Gov. Jared Polis and the governors of five of the six other basin states. California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who cited pre-existing family commitments, was the only governor absent.

The New York Times on Saturday reported that the governors achieved “no breakthrough — and whether they made progress was unclear.” Mitchell was quoted in that story saying upper basin states “cannot and will not impose mandatory reductions on our water rights holders to send water downstream.”

In other words, as she had said Colorado water users must live with the hydrologic realities, including this one of almost no snow. Colorado does not have the giant reservoirs of Powell and Mead upstream.

Others, including Eric Kuhn, the former general manager of the Glenwood Springs-based Colorado River Water Conservation District, have urged a new model based on proportionate cutbacks, not absolute numbers. See: “Dancing With Deadpool on the Colorado River,” Big Pivots. Dec. 12, 2025.

That is how the four upper-basin states among themselves apportioned their share of the river flows in their 1948 compact. The 1922 compact used absolute numbers, i.e. 7.5 million acre-feet for each basin.

The Colorado River Compact of 1922 among the seven basin states uses some language that can be interpreted very differently about delivery obligations. That is a long, involved story — that may eventually be decided by the Supreme Court.

The Arizona Daily Star, however, reported a nuance of possible importance in statements made by Mitchell and Polis afterward. Mitchell emphasized “voluntary” conservation in the upper basin, while Polis said Colorado remained “committed to working collaboratively to find solutions that protect water for our state, while supporting the vitality of the Colorado River and everyone who depends on it.”

An Arizona source told the Daily Star’s Tony Davis that some Upper Basin governors appeared open to possible mandatory, as opposed to voluntary, conservation measures. “I think the other Upper Basin states expressed a willingness to put water on the table in a way that Colorado has not,” said the source, who asked for anonymity to protect continued participation in interstate river discussions.

But again, Colorado insists that it already has mandatory cutbacks — the ones imposed by Mother Nature. Using the prior appropriation doctrine to sort out priorities, Colorado restricts uses even in the more water-plentiful years. This year, the most “junior users” will most definitely not get water.

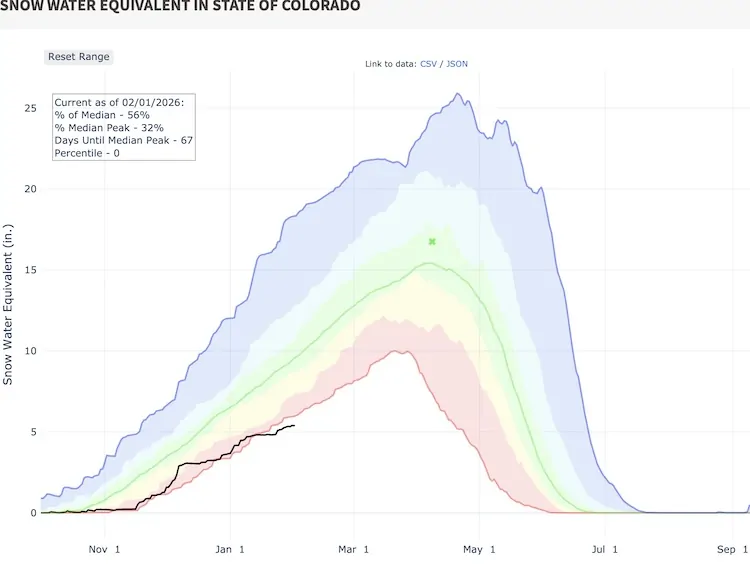

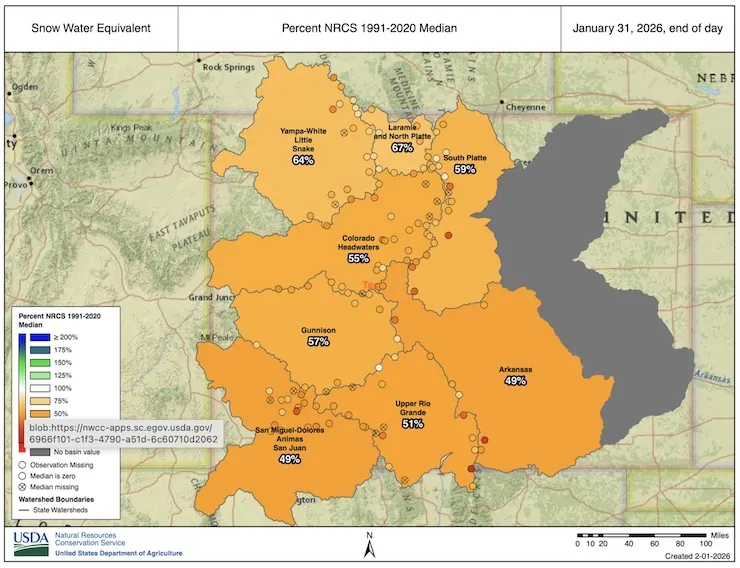

The black line in this chart represents snow-water equivalent in Colorado’s snowpack as of Feb. 1 relative to 1991-2020, a time frame of which about two-thirds consisted of drought and aridification. The map below shows the snow-water equivalent as of Jan. 31 by basin. More can be found at the Natural REsources Conservation Service. Top photo: Becky Mitchell at a forum somewhere in Colorado about two yeas ago.

Amy Ostdiek, the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s chief for interstate, federal, and water information, made that point in remarks at the Water Congress the day after Mitchell’s speech.

“These reductions in the upper basin are mandatory. They’re uncompensated. They’re the job of each state engineer’s office to go out and shut off water rights holders when that water isn’t available. And what that means in practice is that many years you have pre-compact water rights dating back to the 1800s getting shut off.”

The complications of mandatory reduction of water uses also came up in a session with state legislators at the Water Congress.

Ken Neubecker, a long-time Colorado River observer affiliated with environmental groups, said mandatory cuts to Colorado River water use would require an amendment to Colorado’s state constitution and likely those of other upper-basin states.

Colorado’s constitution has been amended repeatedly since 1876, when Colorado achieved statehood, but the provision setting forth prior appropriation has not been touched.

“I don’t think you will get an amendment that will give the state any kind of authority to enact mandatory cutbacks beyond existing administrative cutbacks,” said Neubecker. “That’s just not in the cards.”

The upper-basin states also differ fundamentally with lower-basin states in that the lower basin states have just a few giant diversions, such as the Central Arizona Project and the Imperial Valley. The headwaters states have thousands of legal diverters. That also makes application of mandatory diversions more difficult.

These facts would together make mandatory costs a legal and logistical nightmare to administer.

The states have a deadline imposed by the federal government, as operator of the dams, to agree how to share a shrinking river.

Later this year, Mother Nature may impose an even harsher deadline if current thin snowpack continues to prevail. The statewide snowpack was 58% of average as of late January when the Water Congress conference was getting underway.

One barometer, if imperfect, of the snowpack is the snowpack on Vail Mountain. On Jan. 15, the Vail Daily’s John LaConte reported that the Snotel measuring site at the ski area showed the worst snowpack reading in 44 years of measurements.

The opening of Vail’s Back Bowls also testifies to dryness of the Colorado River headwaters. As recently as 2012, a notoriously dry year, that south-facing ski terrain was not opened until Jan. 19, according to David Williams of the Vail Daily. On Jan. 26, he reported another foot of snow was necessary to open it.

In June 2023, Polis appointed Mitchellto her current position, as Colorado’s first full-time commissioner to the Upper Colorado River Commission. She had previously overseen the Colorado Water Conservation Board.

“Mitchell will now navigate the deep challenges of the Colorado River in this upgraded position, supported by an interdisciplinary team within the Department of Natural Resources and support from the Colorado Attorney General’s Office,” said the announcement.

“The next few years are going to be incredibly intense as we shift the way that the seven basin states cooperate and operate Lakes Powell and Mead,” Mitchell said in that 2023 announcement. “Climate change coupled with Lower Basin overuse have changed the dynamic on the Colorado River and we have no choice but to do things differently than we have before.”

Following are Mitchell’s prepared remarks:

Colorado River is not interested in our agreements of the past

by Becky Mitchell

Let’s start with a truth that somehow still feels radical: The Colorado River is not broken.

We are.

The river is doing exactly what rivers do when you take too much from them for too long. It is responding to reality. And right now, for many, reality is inconvenient.

For more than a century, we built a system of optimism and entitlement. We planned for abundance, labeled it “normal,” and wrote it into law. When the water showed up, we spent it. When it didn’t, we blamed the weather, climate change, or each other—anything except the simple math.

The river never signed those agreements. And it is not interested in our love story with the past.

Lake Powell and Lake Mead were supposed to protect the system. Instead, we turned them into shock absorbers for delay. We wanted them to be savings accounts, when in reality we treated them like credit cards—use now, pay later.

Well, interest has accrued, and the bill has arrived. Both reservoirs are in a treacherous situation.

Lake Powell was never meant to be drained so that hard decisions could be postponed downstream. It was designed to stabilize the system, to smooth out highs and lows; not to prop up demand that no longer matches supply. Year after year, Powell has been drawn down to protect uses elsewhere—even as inflows decline and the margin for error disappears.

Lake Mead tells the same story from the other end. Despite conservation programs, pilot projects, and voluntary agreements, Mead keeps dropping. Not because we lack creativity—but because we are still taking more water out of the system than the river is putting in.

Reservoirs don’t lie. They are the silent accountants of what we actually do, not what we say we’re doing.

Here in Colorado, when the river runs low, the impacts are immediate. We don’t have a giant reservoir upstream to hide behind. Shortages here are hydrologic. They are real. Farmers fallow fields. Municipalities restrict use. Communities adapt — not next year, not after another study or more modeling, but now. These impacts should be the indicator of the level of action that is needed across the entire basin.

That lived experience matters — especially as we head into a post-2026 world.

Post-2026 is not just another chapter in the Law of the River, it is a reckoning.

The (2006) Interim Guidelines were written for a different river — a river of the past. The drought contingency plans were emergency patches — not a permanent fix but to buy time at a cost of more than a billion dollars until the next deal. We all know now those Band-Aids don’t fix holes in reservoirs. And the idea that we can simply extend these frameworks or merely modify them — while Powell and Mead hover near critical elevations — is not leadership. It’s hope, not based on reality or experience, but avoidance.

In the post-2026 world, operations must be supply-based. Not demand-based. Not entitlement-justified. And not built on the hope that the next big year will save us. The harm will be irreversible because the Colorado River is NOT TOO BIG TO FAIL.

Right now, the Basin States have a chance to prevent further irreversible damage and try to avoid bankruptcy. But that will only be possible if we all work together and see the stark reality of our present circumstances with clear eyes. We must build a framework that recognizes and adapts to the math problem–supplies that regularly give us all less than our full rights and entitlements, that improve efficiencies for water intensive sectors, allow us flexibilities to help our neighbors when we can, and require full transparency for measurement, monitoring, and accounting across the Colorado River System to build trust between us. Trust is difficult to rebuild when some don’t acknowledge or adhere to the agreements already made.

That means releases from Lake Powell must reflect actual inflows, not political pressure.

It means protecting critical elevations is not optional.

And it means Lake Mead cannot continue to serve as a pressure valve for overuse.

We cannot manage scarcity with delay.

We cannot store our way out of imbalance with water that isn’t there–that may never be there.

And we cannot negotiate with simple arithmetic, no matter how many times we tell ourselves it will be different this time.

As sparks fly in the interstate negotiations, it is important to keep these realities in mind despite the rhetoric that attempts to distract.

Colorado is often told to “come to the table,” as if we’ve been absent. But we’ve been here the entire time — bringing hydrology, realism, and a simple message: if reductions aren’t real, reservoirs won’t recover. It is telling that what some refer to as an extreme negotiating position is based solely on the simple facts of hydrology — using more than the supply will bankrupt the entire system for everyone. How does the saying go? Doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result is the definition of insanity.

We are not asking for special treatment. We are not asking for a pass on doing our part to help save the system from collapse. We are asking for honesty. For reductions from both basins that are measurable, enforceable, and in proportion to use—not in proportion to who can avoid the truth the longest.

Because if we don’t choose how to live within the river’s limits, the river will choose for us. And it will not be gentle.

This is not a call for conflict. It’s a call to face the reality of this unprecedented situation and come together to manage the river with wise and mature decision-making.

Lake Powell and Lake Mead are no longer warnings. They are verdicts.

They are telling us — clearly and without spin — that the era of surplus, overuse, of clever deals is over.

The question facing all of us post-2026 is simple:

Do we align the rules with the river we actually have — or keep clinging to a past that no longer exists?

So as I head east I take you with me, because I know you all are doing the real work back on the home-front. This year’s current hydrology demands it. I know Coloradans will be prepared, like they always have been. Fields will be fallowed, municipalities will be preparing to manage within their resources, deals will be made to protect fish and flows. Junior priority water users know that years like this one will call for collaboration and innovation, senior priority water users will work within the law and with those that are suffering, you will help each other pay the bill from Mother Nature because you know we all rise and fall together.

You all are here doing the real and hard work, and I will take that with me.

Coloradans should be proud that we are choosing reality over fantasy, science over slogans, and responsibility over delay.

That is not weakness. That’s leadership.

In posts that will follow, Big Pivots will share comments made at the Water Congress conference by:

- Jim Lochhead, a long-time Colorado representative in Colorado River discussions before he was chief of Denver Water;

- Amy Ostdiek, the Colorado Water Conservation Board’s chief for interstate, federal and water information, and

- Colorado Attorney General Phil Weiser.

- How Colorado sees the Colorado River stalemate - February 2, 2026

- Colorado tops 6 million - January 28, 2026

- Difficult decisions on Colorado’s eastern plains - January 26, 2026

Who knows what the Feds will come up with. I’m not a water wonk, but the way I look at agreements that I can understand, the Upper Basin agreed to deliver 75 MAF/10 yrs at Lee’s Ferry, but the inflow to Powell needs to be considerably bigger than that.

There was never an agreement to allocate evaporation from Powell elsewhere, so that needs to be added. The Mexico allocation seems like it adds another 0.75 MAF per year with some wiggle room for drought.

Given those, it seems like the Upper Basin, which is mostly CO, is about at the limit.

While our rep says “releases must reflect actual inflows,” that’s absolutely going to happen with the reservoir level where it is no matter what. The question is whether those inflows will be less than stipulated in the agreements. The other question being how one interprets or re-interprets those stipulations.

I’m more sure of energy. I’m sure there’s more of that to be had. I’m not sure of what to do about the water, but I’m sure there’s no more of that.